Cult art group BANK was active between 1991-2003, when I was holed up at school/university in the provinces and so heard nothing about London culture except ubiquitous YBAs, Britpoppers and later Blair’s champagne socialists, which all seemed tres sexy and escapist.

In retrospect, I still love the era’s hedonism- bratty, self-conscious and ludicrously louche- but this was the obliterating mainstream; I knew nothing about the pranksters and radicals labouring beneath its deadweight. Simon Bedwell, John Russell, Milly Thompson, and sometime-members such as Andrew Williamson and Dave Burrows, were busy baiting the art & popular press as the BANK collective, aiming an anti-canonical water cannon at every establishment going: the swelling art market, sensationalist tabloids, inane pop culture, and dour political collectives. The BANK collective mercilessly taught the artworld a lesson by subverting its etiquette, combining beyond-shitty promotion, anti-curating, and bitchy art pranks like returning gallery press releases disfigured by pedantic corrections (‘Fax-Backs’).

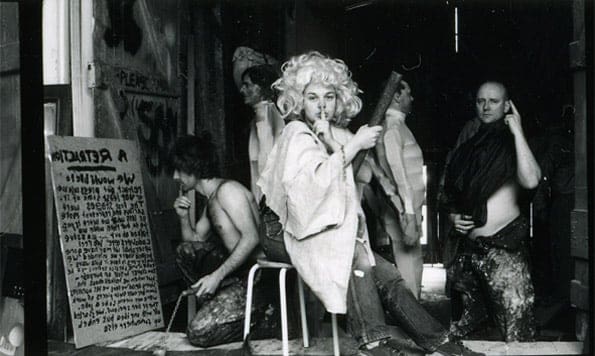

Hoisted from its historical context and prettified in MOT International’s white City gallery, BANK’s work still manages to be shambolic, funny and annoying. Current show The Banquet Years features work from BANK’s 1998/9 period, concentrating on the exhibition “STOP SHORT-CHANGING US. POPULAR CULTURE IS FOR IDIOTS. WE BELIEVE IN ART.”For this exclusive interview I met up with Simon Bedwell and Milly Thompson, who selected work for the exhibition, and maintained the BANK archive for the past decade. I also got fellow troublemaker Dave Beech to stick his oar in; Beech exhibited in four BANK shows, gaining an outsider’s view of the group’s dynamics.

The mischief BANK got up to seems tame now, perhaps only because it made such liberty-taking obligatory. Radicalism always ends up as a new orthodoxy. Is BANK still potent as an archive?

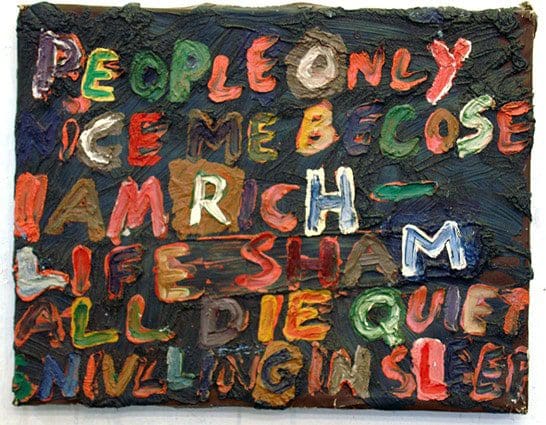

Simon: Mischief is an infantilising, dismissive way of putting it, though I recognise that it may seem to be in the spirit of the forms of our mouthy verbiage. What we said through these various shouty, abrasive, comic etc forms – the manifesto, the tabloid paper, the differently-voiced mailouts etc – remains relevant, arguably: nothing’s changed; artists are still shafted, the curating industry has just got more and more dominant and full of morons, and people still write crap for press releases.

Milly: BANK seems to still stand for radicalism – I’m surprised at the continuing level of interest (and delighted), the work we made still doesn’t look like anything else I think, and maybe there’s potency in something that has not been sort of plagiarised in one way or another.

Dave Beech: All mischief is context specific, so it’s always tame out of context. That’s nothing to do with BANK. Re-presenting or archiving mischief is still important, though. Now it is about knowledge, though, not impact.

A retrospective is never random- why now?

Simon: Random, no; but opportunities need to call. The first time was for a Paris indie space last October, called Treize, when Gallien Dejean there was interested in us; then there was space in the calendar at MOT. The time seemed right, and we’d had a dress rehearsal.

Milly: The show at MOT is not a retrospective. It’s a commercial gallery show with things to sell. The vitrine contains all our press releases and invites etc., and it’s there for context, so maybe it looks a bit retrospective I suppose. A retrospective, would have to be at a large museum with a lot of money to throw at it – with at least three entire BANK shows to make sense at all as a retrospective. I would like to do one in St Bart[holomew].

How did your involvement with BANK come about Dave? Was it product of an old-boy’s network (only with Marxist polys instead of private schools)?

Dave Beech: I was invited by Dave Burrows to a meeting in a bar in the West End not long after the Wish You Were Here show in 1993 [actually ’94]. I don’t remember who else was there, but probably John and Simon and perhaps Bill and Milly, but I can’t say for sure. They already had a year or two’s shows planned and asked me if I wanted to be included in one of several they had titles for: Zombie Golf (I said yes straight away, just because of the title), The Charge of the Light Brigade (I wasn’t as keen), Cocaine Orgasm (I ended up in this one but I thought the title was shit).

David Burrows told me they wanted me in a show because they liked my work but later Simon told me they’d invited me because my presence would bring along the Marxist contingent of the artworld. I only knew David at this stage, so there was no old boy’s network. I knew David through John Roberts. David’s membership of BANK didn’t last into the next exhibition, though, so I was dealing with strangers really.

And how was the curating experience for you?

Dave Beech: The curating, by today’s standards, was almost completely absent. They had a space and they worked in it. I went to see them once before making the work for the show. They had made some lifesize wax figure ‘zombies’ which they thought would take the shine off the work of the artists in the show – their ‘setting’, I was told, was meant to be antagonistic towards the art or the artists. I was writing my MA at the RCA on philistinism so I was sympathetic to this but not as sympathetic to their interpretation of zombies. I made little thought bubbles out of photos of movie posters with slogans such as ‘Life is a terrible thing to sleep through’. I cut them out and hung them over the zombie’s heads, giving them a kind of internal life that is conventionally impossible for them. My intention was to subvert BANK’s subversion of me.

As BANK, did you see your work as being political in any way (aside from attacking the petty politics of galleries)?

Simon: BANK was a melancholy project, and a good part of that would be the acting as if we were political, or rather as if we believed we were, in full and doleful knowledge that it was impossible to be, with any real meaning – in art of course, but also, by analogy, in life. And since then as now, real politics doesn’t seem to be able to talk about anything other than shaving taxes here or there, then maybe art is as likely to have a political effect as anything else – maybe. But anyone who took our rhetoric ‘straight’ we thought was a total idiot; very amusing for us when anyone fell for it though (note this doesn’t mean we weren’t political, either). Gilda Williams wrote that our work was ‘political art in a form we’re just not used to seeing.’ I would add ‘conceptual’ to that, though that’s another word nobody knows the meaning of.

Milly: If I ever thought about politics, it was and is a creeping anxiety about small mindedness, homogenisation, banality etc in everything!

Allegedly, BANK’s token female (Milly) was only invited to attract funding/lefty respect [See ‘BANK’, Black Dog, 2000:12]. You also had titles like ‘TURNER PRIZE BEAUTY PAGEANT’ and ‘BONKERS BIRDS’. What sort of gender politics were at play in BANK?

Simon: You’re falling for our own press in this question. Milly was in BANK from ’93 till the end in 2003, so was clearly pretty central to the operation.

Milly: It was a macho environment. It was carnival-ish. I did sewing and I knew how to use what was then ‘Quark XPress’ (Indesign now) and so I did a lot of the sort of ‘layout’ stuff, but my voice was not relegated to the secretarial pool and I never felt side-lined by the men because of being a woman.

Dave Beech: I don’t know how much BANK ‘cared’ about female participation. They might just have seen this as a necessity given the political circumstances at the time. BANK was really quite laddish. When they invited me to ‘curate’ a section of Dog-U-Mental – Simon phoned and said he wanted me to throw a spanner in the works because the show that they’d planned seemed a bit boring – I asked them what they were doing and the bit that stood out was the section called ‘Bonkers Birds’ – a female-only mini exhibition as part of the whole show. In response I curated ‘Shut Up You Stupid Cunt’ (the title comes from a letter in Time Out from Kathy Burke to Helena Bonham Carter), which was a male-only exhibition in which the contributors were encouraged to bully the other contributors by taking up the majority of the space. I think you could say that the gender politics of BANK and the culture around them was complex but certainly a hot topic.

Artists get special dispensation to be deviant. Was there anything you weren’t prepared to talk about/represent in your time with BANK, Dave?

Dave Beech: The only thing that bothered me about BANK was their apparent conservatism, not their deviance. I loved their deviance. I remember at the time feeling uncomfortable watching a performance by ‘Wayne Winner’ in the character of a sadistic boss getting his secretary to crawl about and do humiliating things. But I trusted Wayne so much as an artist that I watched the whole thing in the hope that I’d learn something about my own limitations.

BANK worked hard to be offensive & relished rubbing galleries and artists up the wrong way. Was there anything more to it than kicking against the pricks?

Simon: See Q1. BANK was simply following the tradition of the avant-garde in this, at exactly the time that everyone was busy trying to be marketwise (see Brit Art). We were always amazed at how people got annoyed (they did). The 2 main mags, Freize and Art Monthly, ignored all our best shows – not one review ’95 till ’98 – and I think this was a direct result of saying the unsayable.

Our targets were art targets, like institutional critique but in a very different form. We spent long hours debating these subtleties, believe it or not, to get the tone right between satire and critique, truth and offence. Except in the Fax-Backs, where we let rip a bit; they were never meant to be exhibited really, at first or by intent, we were just sending galleries back our comments.

Milly: We didn’t work hard to be offensive. If we were offensive it’s because we were just being offensive, or we were careless, or irresponsible maybe, and we did offend some people properly, which I regret. That was never the point – it was always the wider art-world rather than any individual that we were really interested in…I think BANK sensed the coming era (Frieze generation and your own ‘art world as bigger BANK’ below) and though we couldn’t know the shape of it, the artworld jargon, the increasing ‘professionalization’ of it, the YBAs were starting to attract bigger prices than Helen Chadwick or Tony Cragg or Richard Wentworth ever did in the 1980’s, the stupidity of ‘Cool Britannia’ – was hanging over everyone. There was a feeling that something was going to change, and I think we were making work about that without quite knowing it – and that’s why BANK still seems relevant now.

The art world is an even bigger ‘BANK’ now. Is there any way to fight the power of the market? Is it still possible to make BANK-style protests, or has the game changed?

Simon: No, there is no real way to fight the power of the market; but the rhetoric of the fight can fuel artists, so long as it’s fun for them, and makes the art good. But it carries many risks with it – and I think BANK were unique in riding the possible beauty of that risk (name me anyone else who risked looking like they meant it when they described the Freize editor as ‘no oil painting’ etc etc); rich or stupid people will never forgive you if you point out their privilege or stupidity to them; would you?

Milly: By falling in love with it.

Dave Beech: BANK never made protests. BANK changed very little if anything; whatever was possible then is still possible today. The issues have changed only insofar as the market has got bigger, stronger and more powerful. The point, however, is not to protest against the market but to build alternatives to it.

What current artists/collectives do you rate/hate?

Simon: The ones I hate most are those awful ‘we’re doing this on behalf of seriousness and History’ ones, like Otiose Group (sic). This idea of a collective (which BANK Collective were not, we were an art group, a group of artists who collaborated, and who made exhibitions which were art in themselves, rather than arranging temporary meetings of artworks: and collaboration itself has a small-‘p’ political aspect in the way it transforms authorship) has been obnoxiously fetishized, purely for the apparent cachet of the automatic presumption of ‘politics’ it brings with it. I can’t think of one that isn’t just fake and pretentious; it’s always just a pose.

Milly: Jeff Koons, Alex Katz, Martha Rosler

Finally, is the BANK Collective really over?

Simon: Yes; though me and Milly did a little anti-Cameron booklet for Declan Clarke’s ‘Fuck Book’ project a few years back. This current show is not a ‘Showaddywaddy Reform!!!’ situation: John hasn’t talked to me for 13 years, since he had to leave, for a start.

Milly: Yes.

[Disclaimer: Due to necessity, all three interviews were conducted in isolation; hence statements should not be misread as responses to each others’ answers.]

words Vienna Famous