by Charlotte Hopson

If there was an artist that could perfectly emulate our masturbatory; that is self-gratuitous, consumerist and commercial culture, then Damien Hirst would be the perfect representative.

In the near quarter century, since he provocatively and uncompromisingly burst onto the art scene back in 1988 with the now infamous first exhibition Freeze, which he conceived and curated for himself and fellow Goldsmith art students and friends, [many of which would later form the yBas]; Hirst has been responsible for inordinately changing the look, the meaning, but perhaps most saliently: the value of art.

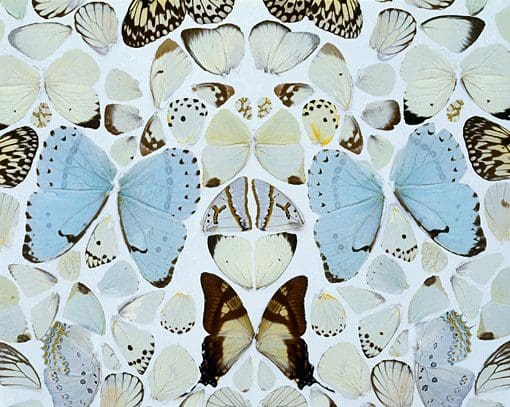

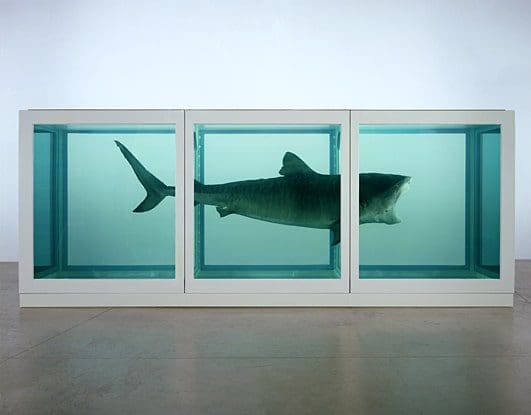

Best known for his iconic diamond encrusted skull, For the Love of God (2007), which reportedly cost an enormous £14 million to produce; his largely assistant-produced spot and butterfly paintings, and his macabre penchant for suspending various pickled animals in formaldehyde, such as The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), Hirst has created some of the most recognisable and expensively produced works in contemporary art to date. However, his notoriety has invited reverence and revilement in equal measure. He has been criticised for creating works specifically with hedge-fund or celebrity clientele in mind, and thus depreciated artistic value in favour for cash appeal. Although his artworks have become highly sought after collectables, it is as much for their association with Hirst as a celebrity artist, than as desirable goods for spectacle purpose; as Brian Sewell has written recently: ‘to own a Hirst is to tell the world that your bathroom taps are gilded and your Rolls Royce is pink.’

This association with money and excess came to a climax back in 2008, when Hirst made the unprecedented move to bypass his long-standing galleries, and sell an entire show, Beautiful Inside My Head Forever at auction at Sotheby’s, which exceeded all predictions and raised a record-breaking £111 million. This was a pivotal moment in the history of the global art market, and has since redefined the commodity value of the art piece. However Hirst’s prioritisation of money has truly come at a price, as his oeuvre has been characterised by financial exchange, both by money spent on production and of price reached at sale, rather on artistic merit. This has also been aggravated by contentions to Hirst’s legitimacy as an artist. His career has been plagued by various accounts of plagiarism throughout the years, and his controversial methods of artistic production have been consistently contested. Hirst’s unashamed employment of huge teams of fixed-wage assistants in production-line studios, a sort of ‘Haus of Hirst’ if you will, responsible for the actual creation of his art, [yet who enjoy none of the monetary excess,] has sparked consistent critical debate, and foregrounded the questionable authenticity of his works. Nevertheless his shows continue to sell out and his highly collectable and exorbitant artwork sale prices, confirm that no matter the creative process, Hirst is unquestionably one of the most renowned and commercially successful British Artists working today. So when Tate Modern revealed that they would be hosting the first major survey of Damien Hirst’s work, there was no doubt that this would become one of the most hotly anticipated and talked about exhibitions of 2012. So far it hasn’t disappointed. Critics in their dozens have once again returned to review the artist’s controversial backlog of unprecedented sales and reignited critical debates. However, as interesting as these views might be, nothing is better than forming your own. So with an open mind, I went to experience this unique retrospective.

This show has been four years in the making; with head curator Ann Gallagher working closely with Hirst to create a show which chronologically traces artworks created during the artist’s career between 1986- 2008. All works displayed have been constructed onsite, and include, a remake of the shark in formaldehyde [now with mouth open], Mother and Child Divided, (2007) the bisections of a cow and her calf; his spin paintings; a room encapsulating the life and death cycle of butterflies, [a room proving popular with the children]; various cabinets filled with medicinal packages; a room transformed into a pseudo-pharmacy; and countless butterfly and spot paintings and more. Naturally one assumes that a survey of this kind should present an opportunity to trace artistic development and to witness an evolution of ideas; however, it seems that for Hirst, this collection of work in fact exposes his conceptual stagnation. Although rooms 1- 14 present works which explore monumental themes including life, death and dualities of beauty and horror, Hirst’s application is gaudy and superficial, leaving nothing to the imagination, and thus negating any potential for further investigation. Hirst has said that his art is ‘not made with meaning in mind,’ that they are ‘just triggers for people to input meaning,’ but I believe this to be a lazy motivation which has ultimately resulted in shallow artworks, which conceptual artistic intention could and should have replenished. The only work which I feel is truly engaging, is A Thousand Years, (1990); a double vitrine in which maggots, develop into flies, which congregate and feed on a rotting cows head, and then when unfortunately enticed, zapped by the insect-o-cutor suspended directly above. It is a kind of nihilistic, microcosmic universe, in which the determined cycle of life, sustenance and death has been apathetically encapsulated. Wafts of decaying flesh provide an unwelcome but powerful sensory dimension to this otherwise visually compelling work; however, it is as Lucien Freud said to Hirst about the piece: “I think you started with the final act, my dear.”

This survey provides a collection of works, which are essentially variations of each other. The frustrating repetition of taxidermy, vitrines, medical supplies and instruments, and spot paintings, left no real impression other than an exhaustive list of artworks mildly concerned with already overworked and underdeveloped ideas. Each display seems to be bigger and much shiner, yes, but essentially versions of the same product. It is disappointing to realise that over the course of twenty-two years, Hirst’s work essentially stalled from the beginning. It seems that the only progression has been Hirst’s increasingly blatant lucre, his overzealous grandeur and prioritisation of commodity value. However, this is not to say that aesthetically I did not enjoy the show. If considering a piece individually and independently from its neighbour, then sure enough, it’s highly finished and perfected composition accounts for [an albeit slightly pointless] decorative and visually pleasant artwork. However, as one of our nation’s most renowned artists, his collection of work is a little underwhelming and lack lustre. It seems that when Hirst made his name and the money came rolling in, he sold out; endlessly reproducing production-line artworks such as the mind-numbing spot paintings- putting in little effort for maximum gain. He has certainly cashed in on people’s eagerness for branding and susceptibility to publicity, and in that way his mastery has been his manipulation and careful construction of his art as a business, rather than as a practise. Perhaps in his death he will get his assistants to diamond encrust his pickled grinning face, suspended in formaldehyde in a gilded, butterfly decorated vitrine and call it The Inevitability of a Record Breaking Sale of an Artist who is Now Entirely Spent.

Tate Modern: Exhibition, Until 9 September 2012 – £14, concessions available

Open late Friday – Sunday until 22.00 www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern

Artist Feature by Charlotte Hopson